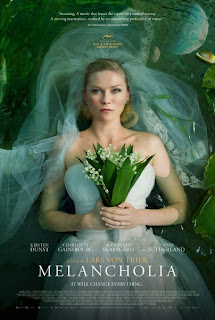

"Melancholia" Beautiful, Sprawling Apocalypse

Melancholia (2011)

130 min., rated R.

Danish film auteur Lars von Trier continues to vie for our attention by making arthouse films about fragile, masochistic women. If 2009's punishingly pompous "Antichrist" was his horror film, and an angry, arrogant reaction from the director's publicized depression, then "Melancholia" is his sci-fi disaster movie and hopefully results in no relapse of a mental breakdown. This one has no slicing of female genitalia, but it's as visually mesmerizing and emotionally hopeless as the end of days could be. What with Terrence Malick's "The Tree of Life" and Mike Cahill's "Another Earth," it seems the most ambitious of filmmakers had a mutual epiphany: play a family drama against cosmic events. Casting a spell with an otherworldly beauty and sprawling vision, von Trier's "Melancholia" is a beautifully profound meditation on depression and human existence.

Split in half, Part One: Justine and Part Two: Claire, the story follows two sisters that each represent different reactions to the portent of an apocalyptic event, whether it be emotionally unstable or keeping it together on the outside. Arriving late to their own wedding reception, Justine (Kirsten Dunst) and Michael (Alexander Skarsgård) have one of their last laughs maneuvering the limo through a winding, narrow driveway to the luxurious home of her level-headed older sister, Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), and money-minded husband, John (Kiefer Sutherland). After Claire and John chide them for being late, the calamities pile up and Justine begins to deliberately sabotage her own newly wedded bliss. Michael's best man and Justine's boss, Jack (Stellan Skarsgård, Alexander's real-life father), promotes the bride to art director at their advertising firm, but then has his minion (Brady Corbet) follow her around to get a campaign tagline out of her. Justine also feels alienated from her parents: her mother (Charlotte Rampling) is so bitter that she won't give a speech but stands up from her seat anyway to disparage the idea of marriage, and her randy father (John Hurt) is so preoccupied with his lady guests named Betty. At one point, Justine drifts away from her own party, taking a golf cart to stare at a red star in the sky and urinate on the golf course. After returning to start the celebration, she exits again to put her nephew to bed, only to fall asleep, and right before she's scheduled to cut the cake she's bathing in the tub. Justine can only keep her fake smiles up for so long. By the end of their wedding night, Michael leaves his alienated bride.

In Part Two, Claire is still nursing and reassuring Justine, but eventually becomes the sick one as fears the blue planet of Melancholia will collide with our own. As a doomsayer, Justine might know things others do not, like the unavoidable coming of doomsday. Set to the prelude of Richard Wagner's classical opera Tristan und Isolde, the film's prelude is a stunning tableaux of majestic, painterly postcards at hyper-slow speed. The camera centers on a dazed Dunst's long face as birds fall from the sky; the bride herself weighed down by not only her wedding dress train but the vines and roots of a forest green; Claire, with her son in her arms, trudging through the quicksandy golf green; and Melancholia encroaching upon Earth.

Wry and penetrating, the first half plays like "Rachel Getting Married," depicting the ceremonial dinner, awkward toasts, celebration on the dancing floor, with even fewer smiles toward the end. It's by far the more interesting of the two, as the latter half palls a bit but at least builds vividly to the inevitable rather than unraveling into insanity. The film is such a visually and aurally striking achievement, with Manuel Alberto Claro's handheld cinematography so intimate and the effects a magical work of cinematic art, that it deserves to be seen on a huge screen the way it was intended.

Much of the film's accolade goes to the performances von Trier pulls out of his actors whose characters' swapped personas are direct metaphors to Melancholia's collision with Earth. We know so little about Justine and some of her cruel actions are out of nebulous illogic that it's nearly impossible to connect at first. But then again, depression is not always easy to explain. The ambiguity on the page forces Dunst to delve even deeper into the skin of Justine, delivering a performance that's the farthest from one-note. Happy to manic-depressive and self-destructive to vulnerable and then finally a 180 degree turn at ease, she articulates every complex, uninhibited emotion with her face rather than words. Winning herself an award for Best Actress at the Cannes Film Festival, Dunst has never shown what she could fully offer dramatically until now. This is the performance of her career. In the "Claire" section, when Claire runs a bath for her sister, Dunst's depiction of her heavy-footed, catatonic state is jaw-dropping. Her on-screen bravery even extends to another nude scene she performs while moon-bathing by a riverbank. Gainsbourg has less to bare than her last time working with von Trier on "Antichrist," but takes over the heavy lifting in Claire's section and still commits to her role with raw authenticity.

Emotionally distancing at times but never ice-cold, "Melancholia" proves von Trier has finally found a soul and a point in himself as a filmmaker. This time, depression has brought out the best in him, but now Mr. von Trier, take your Lexapro.

Grade: B +

Grade: B +

Comments

Post a Comment